Craft Q&A

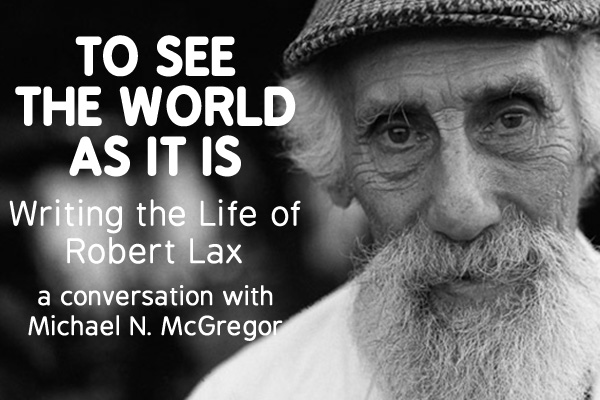

ichael N. McGregor’s first book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, is the story of poet Robert Lax, whose quest to live a life as both an artist and a spiritual seeker inspired Thomas Merton, Jack Kerouac, William Maxwell and a host of other writers, artists and ordinary people. Known in the United States primarily as Merton’s best friend, and in Europe as a daringly original avant-garde poet, Lax left behind a promising New York writing career to travel with a circus, live among immigrants in post-war Marseilles, and settle on a series of remote Greek islands where he learned and recorded the wisdom of the local people. Born a Jew, he became a Catholic and found the authentic community he sought in Greek Orthodox fishermen and sponge divers.

ichael N. McGregor’s first book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, is the story of poet Robert Lax, whose quest to live a life as both an artist and a spiritual seeker inspired Thomas Merton, Jack Kerouac, William Maxwell and a host of other writers, artists and ordinary people. Known in the United States primarily as Merton’s best friend, and in Europe as a daringly original avant-garde poet, Lax left behind a promising New York writing career to travel with a circus, live among immigrants in post-war Marseilles, and settle on a series of remote Greek islands where he learned and recorded the wisdom of the local people. Born a Jew, he became a Catholic and found the authentic community he sought in Greek Orthodox fishermen and sponge divers.McGregor met Lax in 1985 while traveling in Europe and visited him regularly over the last fifteen years of the poet’s life. McGregor and I talked about the challenges of writing the story of a quiet, solitudinous man who has, until now, mostly appeared as a footnote in the lives of others. —Dan DeWeese

Propeller: When did you first start thinking about writing a book about Robert Lax, and how did you get started?

Michael N. McGregor: The thought to write a book about Lax came to me a few months after his death in September of 2000. I had just been hired into a tenure-track position at Portland State University teaching nonfiction writing and needed a nonfiction book project. Lax, whom I had known for fifteen years, had lived a fascinating life and was the wisest man I’d ever met. Both his poetry and his life were far less known than they deserved to be and what had been written about him often included significant errors. I saw writing about him as an opportunity not only to set the record straight, but also to dive more deeply into intriguing parts of his story, such as his friendship with Jack Kerouac, his work for The New Yorker, his screenplay writing in Hollywood, and his influence on the important spiritual figure Thomas Merton, who was his best friend.

Propeller: What other books did you consider to be models for the kind of book you wanted to write?

McGregor: I thought at first I'd write a straight biography, with little of me in it, except perhaps in a prologue. I wanted my book to be a full, serious biography rather than a memoir, as my agent at the time kept referring to it. As the writing developed, though, I felt it was false to leave myself and my relationship with Lax out of the story when I had known him so well for all of those years and been deeply influenced by him. I began to search for less-conventional biographies. I was already thinking of fictional models such as The Great Gatsby, Lord Jim, and The Good Soldier, books I had long loved that are really fictional biographies. In each of them, the narrator knows the man he is talking about and uses his relationship to the man as the starting point for exploring his life and character. I wasn’t able to find an actual biography that did anything like this except a few often-dubious books by people who had been friends with famous writers and wrote about those friendships.

McGregor: I thought at first I'd write a straight biography, with little of me in it, except perhaps in a prologue. I wanted my book to be a full, serious biography rather than a memoir, as my agent at the time kept referring to it. As the writing developed, though, I felt it was false to leave myself and my relationship with Lax out of the story when I had known him so well for all of those years and been deeply influenced by him. I began to search for less-conventional biographies. I was already thinking of fictional models such as The Great Gatsby, Lord Jim, and The Good Soldier, books I had long loved that are really fictional biographies. In each of them, the narrator knows the man he is talking about and uses his relationship to the man as the starting point for exploring his life and character. I wasn’t able to find an actual biography that did anything like this except a few often-dubious books by people who had been friends with famous writers and wrote about those friendships. Then I picked up a book called The Quest for Corvo by A. J. A. Symons. Symons didn’t know his subject, the author Frederick Rolfe, but he had read one of his books and was curious to know more about the man. Rather than presenting only the results of his inquiries into Rolfe’s life, Symons included his search for facts and a deeper understanding of Rolfe’s character. This freed him from writing in the God-like way most biographies are written, starting with the subject’s ancestry and ending with his death and legacy. The Quest for Corvo reads more like a murder mystery in which you see the murder first and then follow the detective as he searches for answers not only to why the murder happened, but also who the man who was murdered really was. My book doesn’t begin with a murder but rather with when I met Lax. The reader encounters this older man who is full of wisdom and life and, I hope, wonders, as I did, how he came to be the person he was. The rest of the book is my quest for answers to this question.

Propeller: You already knew quite a bit about Lax when you started working on the book, so what kind of surprising or interesting items did that quest reveal about him? And did the quest take you places you hadn’t anticipated?

McGregor: I knew the outlines of Lax’s story and what he was like as an older man, but I didn’t know the motivations for his many moves and decisions except in the broadest terms. A lot of things I discovered surprised me, and virtually everything was interesting. He had told me he’d been friends with Kerouac, for example, but I was surprised to find how strong that friendship was and its effect on Kerouac’s life. I knew Lax’s uncle had been involved with Theosophy and lived in Hollywood, but I was surprised to find he’d been John Barrymore’s business manager and his wife, the first “psychic to the stars,” had designed a house lived in by Charlie Chaplin and then Mary Astor’s parents. I found these kinds of fascinating connections sprinkled throughout Lax’s life. One discovery I treasured was his lifelong correspondence with New Yorker editor William Maxwell, which was filled with tenderness and wisdom.

Propeller: That’s fascinating, because Lax became a poet living in remote locations, working over decades to develop a personal poetic aesthetic at a vast distance from the social centers of the literary world, while Maxwell’s name, to many people, connotes a lifelong New York/New Yorker sophisticate—a literary insider. What kind of things did these two men discuss in their letters? What attracted them to each other?

McGregor: I’ll answer the second question first: They met when Lax worked at The New Yorker in 1941. They were both young, sensitive men trying to figure their way forward in the New York literary world. Maxwell had a knack for taking care of writers and I think he saw right away that Lax needed caring for, but I feel it was mostly that sensitivity married to intelligence and a keen sense of humor that drew them to each other. All I know of their early conversations is that Lax told Maxwell at a party once that he should go home and make a baby, or something to that effect. Maxwell refers to the incident more than once in their correspondence, saying that his first child was the result. Their earlier letters are brief because they often saw one another when Lax was in New York, but later, when Lax was ensconced in Greece, they sent each other quotidian details of their lives, things they had done and seen, usually in the form of anecdotes, salted with casual wisdom. Lax sent Maxwell poems and photographs and copies of his journals—and, later, his books—and Maxwell praised the evocations of circuses, islands, and contemplative life. My guess is Maxwell liked receiving these reminders that someone he respected was living the kind of life Lax was, and Lax was pleased to maintain a connection to the New York literary world, but in the end it was the person each knew the other to be that kept their correspondence going. Maxwell once wrote, “To the best of my understanding, a saint is simply all the things that he is.” And in a letter Lax sent Maxwell late in life, he wrote, “What I usually feel about your letters—and do again today—is that it’s worth having lived all this time to get even one of them.”

La Salette, France. Lax preferred isolated, contemplative locations far from the centers of literary culture.

La Salette, France. Lax preferred isolated, contemplative locations far from the centers of literary culture.Propeller: I interrupted you, though—I’d also asked whether the act of researching Lax’s life took you to places or locales you hadn’t anticipated.

McGregor: My two biggest discoveries, I suppose, had to do with major moves Lax made that puzzled me. He often talked about his life on Kalymnos before he moved to Patmos. I didn’t know until I’d done quite a bit of research that he was, in essence, in love with the people of Kalymnos. He viewed the fishermen and sponge divers there as an ideal society, the living embodiment of his idea of “pure act.” I wondered why he would leave a place he loved so much until I discovered that the people there turned against him during the Cyprus crisis, when Turkish troops invaded Cyprus and the Greeks feared war. Some of his neighbors thought he was a spy. He stayed away from Greece for three years after that, living for a while in the Canary Islands.

The second big discovery came on a Friday afternoon when the Columbia University archives, where some of Lax’s papers are held, were about to close and I was at the end of a two-week research trip. I knew Lax had worked for The New Yorker and published ten poems in that magazine when he was still in his twenties. How, I wondered, did he go from such a high-profile beginning to being an admired but little-known poet? In the archives that afternoon, I opened a box I hadn’t looked at before and found a journal from 1941, the year he worked for The New Yorker. I realized as I read that the threat of being drafted—as a pacifist—and his dislike of commercial magazine work resulted in a brief breakdown. He recovered from it by volunteering at a Catholic charity in Harlem, where he came to eschew ambition and embrace poverty.

I don't know that my quest for information took me physically to any place I didn’t expect—or at least hope—to go. But visiting Kalymnos, where I found someone who had known him there, and locating the building he lived in in Marseilles helped me to see his world better. I guess the one place I never thought I’d get to was the sanctuary of La Salette, high in the French Alps, where he once felt at home. Then a French friend with a car offered to take me there. Again, it was seeing the landscape, experiencing it myself, that helped me understand a side of Lax I hadn’t understood entirely before—in this case, the peace he felt living in a remote location.

Propeller: Remote locations obviously offer a writer time and space in which to work without the interruptions of a distracting social situation, but that doesn’t seem to be all that was going on with Lax—when you say “the peace he felt,” it seems like it was more than just the peace of finding a quiet place to work on some poetry. What do you sense he was finding, or that he needed, from these locations? Were there common qualities you found among the places Lax lived for extended periods of time?

McGregor: At one point in my book I talk about Lax being equally attracted to the energy he found in cities and the peaceful solitude more readily available in more remote places. He was by nature a contemplative—a poet, yes, but someone who thought deeply about things and prayed and meditated, too. He had a hard time doing this to the degree he desired if he couldn’t choose when to be with others and when to be alone. At the same time, he liked to be near a community that shared his faith and values. La Salette provided that kind of atmosphere, as did Kalymnos. In both places—and Patmos, as well—nature is always part of your awareness, too.

Propeller: How do you feel about the way Lax is presented in books about Thomas Merton? What does his treatment in those books capture about him that feels true, and what seems lacking or off when he appears as a supporting character in books about Merton, as opposed to the way you’re able to present him in your book, in which Lax is the main subject?

McGregor: First of all, I’m grateful that Merton wrote lovingly and at length about Lax in his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain. That’s where I first discovered Lax and it’s still the only reason many people have heard of him. Because Merton credited Lax with having a profound effect on his own spiritual development, many Merton readers are intrigued by him. But while most Merton biographers give Lax his due as an early influence on Merton, they tend to ignore him after Merton enters the Gethsemani monastery at twenty-six, and their picture of him is the one Merton drew, of an awkward but fiercely intelligent, highly sensitive and spiritually aware man. They neglect or aren’t aware that Lax continued to be a very important person in Merton’s life through letters and occasional visits, serving as both a longtime confidant and a model for how to live a simple, spiritually oriented life. Although they usually call Lax a poet, they neglect or aren’t aware of the influence his later, more experimental poetry had on many other poets.

McGregor: First of all, I’m grateful that Merton wrote lovingly and at length about Lax in his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain. That’s where I first discovered Lax and it’s still the only reason many people have heard of him. Because Merton credited Lax with having a profound effect on his own spiritual development, many Merton readers are intrigued by him. But while most Merton biographers give Lax his due as an early influence on Merton, they tend to ignore him after Merton enters the Gethsemani monastery at twenty-six, and their picture of him is the one Merton drew, of an awkward but fiercely intelligent, highly sensitive and spiritually aware man. They neglect or aren’t aware that Lax continued to be a very important person in Merton’s life through letters and occasional visits, serving as both a longtime confidant and a model for how to live a simple, spiritually oriented life. Although they usually call Lax a poet, they neglect or aren’t aware of the influence his later, more experimental poetry had on many other poets. I wanted my book to do three things in this regard, I suppose: one, to show that Lax deserves to be appreciated as a significant spiritual figure in his own right; two, to show his importance as a poet with a distinctive and influential approach to poetics; and three, to show that his development as an artist was inseparable from his development as a spiritual person. There is a tendency in some Merton-based writing about Lax to turn him into an almost ethereal, saintly figure. I wanted to show the struggles and decisions and faith and character that created this loving, grace-filled and, yes, saintly man. And I wanted to show that he was a physical being, too, full of laughter and liveliness, a mentor to many and a great friend.

Propeller: One of the things that strikes me in the book is the role Catholicism played in the lives of both Merton and Lax. In popular—or maybe just reductive?—conceptions of current American politics, Christianity is often aligned with conservative politics, as are, supposedly, the interests of “business.” But both Merton and Lax seem to have considered their faith in some ways radical, or at least a means of resisting larger cultural forces. Is it right to read their faith as, in part, an act of political resistance? Or is the role Catholicism played in their lives—especially their creative lives—a kind of wholly other track that we can’t read through the lens of current American politics?

Ad Reinhardt, Thomas Merton, and Robert Lax at the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani in 1959.

Ad Reinhardt, Thomas Merton, and Robert Lax at the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani in 1959.McGregor: When someone asked me about Lax’s politics at a reading, I said he was apolitical. An audience member emailed me afterward and suggested, gently, that I was wrong. Lax’s politics centered on the pursuit of peace and community, this person said. I think that’s true, for both Lax and Merton. Their faith led them to believe even more strongly than they had before that all of life is one and holy. Neither had anything to do with bipartisan politics, but Merton became the spiritual conscience of the anti-war and anti-nuclear movements in the 1960s. And Lax published a broadside called Pax, devoted to the idea that artists making art are by that act promoting peace. Lax moved from America in part to escape the dehumanizing effects of our overwhelming “business” culture: the emphasis on accumulation, commercialization, and “getting ahead.” That, I suppose, is a kind of political act. And it was certainly inspired by his faith: his belief in the truth of the Beatitudes with their emphasis on blessings flowing to the poor, the pure, and peacemakers.

The idea that Christians are automatically aligned with conservative politics in this country is false, by the way. Yes, many evangelicals and fundamentalists lean that way, and because they often make noise, they get a lot of media attention. But Christians have always been at the forefront of American progressive movements and still are today. Go to any meeting of people working to promote community and health care coverage or fighting climate change and weaponizing of the world and you’ll find large numbers of Christians. Or, taking things to a higher level, look at the current pope and what he promotes, how he lives. These are people who take their cues from the words and life of Jesus, not end-times theorizing or biblical literalism or the so-called “prosperity gospel.” They believe that all of life matters, all people and all other living things on Earth.

Propeller: I sense in many literary conversations a kind of passing-over of the religious beliefs of certain writers or artists in favor of discussions of what I guess we might call more “craft-oriented” issues, like looking at a writer’s formal decisions or the structure of a piece. What has your experience been of attempting to talk about issues of faith in literature? Is contemporary American literary culture—if that is a thing—open to talking about those issues? Are readers familiar enough with religious texts to have a context for those discussions?

McGregor: You’ve pinpointed what I think is a real problem in contemporary literary discourse. I recently gave a talk at the University of Notre Dame called “The Language of Spiritual Literature in a Post-Religious Era.” One of the points I made was that open discussions of religion or spirituality are rare in literary circles. Writers of literary works who write from a faith perspective either don’t mention their faith or talk about it in a circumspect way. One of the reasons for this, I think, is the extreme skepticism toward religion and spirituality in many of those who review books or manage the national literary conversation in other ways. My book was one of only a handful of books that deal with spirituality in a positive way to have been reviewed by the New York Times in recent years and even then the reviewer was scornful of its spiritual aspects. In my Notre Dame talk, I cited an article that appeared in the Times in 1965 in which Edward Albee talked openly about being a Christian. I don’t think he would do that today. This is strange because the language of mystery, which is central to both religion and art, is inherently spiritual. I do see glimmers of change, though It seems okay now for a writer to say that she’s Buddhist, for example, maybe because Buddhism comes from outside a Western context. And when Poetry editor Don Share interviewed me about Lax during an appearance in Chicago last year, he made it clear he considered the spiritual context a vital part of understanding the power of Lax’s poetry. I don’t think readers have to be familiar with specific religious texts for a broader discussion to take place; they just need to stay open to different perspectives and the questions that come from them.

Propeller: Your point about Buddhism possibly being “okay” because it comes from outside a Western context is interesting. Do you have a sense of why Western religion has often been dropped from contemporary literary discourse?

McGregor: I’m not sure why. It might stem from the rise of the Christian right in the late 1970s, its use of religion in service of a political agenda alienating the more liberal elements in literary circles. It might come from greater aggressiveness on the part of those without faith in a god, who have sought to “rationalize” what is considered good literature. It might simply be Western religion’s failure to embrace new language and new approaches to faith that might challenge old doctrines. I suspect that Western religion has come to be seen by many as outmoded superstition, inconsistent with intellectual thought. And of course many intelligent and creative people have been scarred by the worst aspects of religion in their families and communities. The spiritual aspects of religion often get tangled up with bigotry, prejudice and even abuse. But those spiritual elements are still there and still worth exploring.

Lax’s “Hermit’s Guide to Home Economics,” published by New Directions.

Lax’s “Hermit’s Guide to Home Economics,” published by New Directions.Propeller: I think it’s fair to assume that many people reading this will not have read Lax’s poetry before. What kind of connections do you see between Lax’s spiritual life and the form and content of his poetry? What in the aesthetics of his poetry do you find somehow reflective of—or maybe just consonant with—his spirituality?

McGregor: A critic once wrote that Lax’s poems “have the force to imply that everything is capable of being transformed into symbolic meaning by coming into contact with a passionate human being.” I think Lax’s great desire was to see the world as truly as possible, not from some objective position, but as the individual he was. He believed deeply in the is-ness of the world and of the moment, and he wanted to capture these as truly and simply as he could. He eschewed more obviously metaphysical poetry because he believed it was enough to see the world as it is to sense its transcendent nature. He didn’t believe in a distant God but one who is manifested in the world, suffusing it with love. He himself was part of that world, filled with the same love In the quiet in his room, as he once told me, he was trying to hear his soul talking to itself, down in the deepest parts of his being where he believed God speaks to us. His poetry was his attempt to capture the quicksilver nature of this talk, this vision, this moment.

Propeller: You spent quite a bit of time with him after he’d already begun to work in the vertical form he’s now known for. Did you have a sense that he was satisfied with that form’s ability to capture that quicksilver nature? He had written for many years in search of a form, so I’m wondering if formal experimentation was something he remained engaged in or thought about, or if his focus moved into other aspects of poetry in the later years of his life.

Robert Lax and Michael McGregor outside Lax’s house on the Greek island of Patmos in 1992.

Robert Lax and Michael McGregor outside Lax’s house on the Greek island of Patmos in 1992.McGregor: I think Lax had decided that the vertical form was the best one for him, for what he was trying to say and do. He was more interested in seeing what he could do with it than experimenting for experimentation’s sake. He did write in other forms in his later years, but they tended to be more prose-like. His great work “21 Pages,” for example, is a meditation on how to live and the meaning of life that uses different approaches to dialogue and sectioning and internal monologue, making it hard to classify. Although most of his writing was done in his signature vertical form, he had stopped thinking much about form or genre, preferring to let whatever he had to express come out in whatever way it did.

Propeller: Are there poets you feel extended or moved forward from Lax’s work, formally or in other ways? Are there “Lax-ian” poets who worked in his wake, or was he unique? What influence do you feel his work has today?

McGregor: I think there are poets who have learned, and are still learning, from his approach. The other day an accomplished poet told me she wanted to go even further than Lax and write one-word poems. It’s the spareness of his work, the impulse toward simplicity that is both profound and memorable, that seems to inspire the poets I’ve talked to. They don’t necessarily want to emulate him but they feel inspired to question the more opulent aspects of their own work. That’s good because those who do try to emulate him do so at their own peril. His writing can seem deceptively easy and imitations can sound hackneyed or forced. One poet who has definitely learned from him and yet gone in his own direction is my Portland State colleague John Beer, who was Lax’s literary assistant in Greece for a couple of years. Beer’s work is challenging and refreshingly different, influenced by Lax but not derivative. In the long run, I think Lax’s influence will be the same as that of other great experimental poets: encouraging younger poets to do things their own way, pushing against accepted notions of line and rhythm and even metaphor. Lax asked himself “What is poetry?” and came up with his own definition—his own way of singing about the world as he saw it.

Michael N. McGregor’s essays, articles, short stories and poems have appeared in publications including The Seattle Review, StoryQuarterly, Poetry, Notre Dame Magazine, The Crab Orchard Review, The South Dakota Review, Image, Weber: The Contemporary West, Poets & Writers, The Writers’ Chronicle, American Theatre, The Mid-American Poetry Review, Portland Magazine, The Merton Seasonal and The Merton Annual. He has also contributed chapters to The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Now Write! Nonfiction: Memoir, Journalism and Creative Nonfiction Exercises from Today’s Best Writers and Teachers, and Europe 101: History and Art for the Traveler. His first book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, was published in September 2015 by Fordham University Press.

Michael N. McGregor’s essays, articles, short stories and poems have appeared in publications including The Seattle Review, StoryQuarterly, Poetry, Notre Dame Magazine, The Crab Orchard Review, The South Dakota Review, Image, Weber: The Contemporary West, Poets & Writers, The Writers’ Chronicle, American Theatre, The Mid-American Poetry Review, Portland Magazine, The Merton Seasonal and The Merton Annual. He has also contributed chapters to The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Now Write! Nonfiction: Memoir, Journalism and Creative Nonfiction Exercises from Today’s Best Writers and Teachers, and Europe 101: History and Art for the Traveler. His first book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, was published in September 2015 by Fordham University Press.