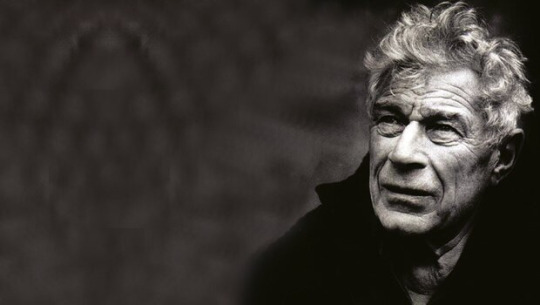

Readings

Always, John

In Memoriam, John Berger 1926-2017

By M. Allen Cunningham

“A presence, a visible presence, is sometimes most eloquently conveyed by a disappearance.” —John Berger

n the spring of 2015, by the good graces of mutual friends, a small parcel traveled from my home in Portland, Oregon, to John Berger’s home in France. Included in the parcel was a brief letter:

n the spring of 2015, by the good graces of mutual friends, a small parcel traveled from my home in Portland, Oregon, to John Berger’s home in France. Included in the parcel was a brief letter:“Because I have read, admired, and drawn immense inspiration from your work for many years now, I feel I have simply too much to say to you — and hardly know where to start — so I will let the enclosed book do the saying, mostly. … There are some few glistening gossamer threads linking this work to yours. Without those strong fibers, I’m not sure the book would ever have been imagined.”

That book was Partisans, a philosophical novel in which Janos Lavin, the main character from John’s own debut novel A Painter of Our Time (1959), is referenced as a real artist. But that’s just one point of connection. John’s body of work inspires Partisans throughout and I wanted him to know this. Since I’d published Partisans myself in samizdat fashion — there would be no promotion and no reviews — he would only know if I told him.

That book was Partisans, a philosophical novel in which Janos Lavin, the main character from John’s own debut novel A Painter of Our Time (1959), is referenced as a real artist. But that’s just one point of connection. John’s body of work inspires Partisans throughout and I wanted him to know this. Since I’d published Partisans myself in samizdat fashion — there would be no promotion and no reviews — he would only know if I told him.At first I wasn’t sure how to address my letter. We’d never met, but “Mr. Berger” wasn’t right, nor was “Dear John.” After much thought, I settled on “Dear John Berger.” It felt most natural, finally, to rely on the name’s printed incarnation, the name as it appeared in all those books I’d been reading for so long.

John’s reply arrived a few weeks later, a handwritten note in a small white envelope. He’d signed himself “Always, John.” That’s how I think of him now, so that’s how I write of him here.

n British television in 1972, standing in a room of the National Gallery, John reached up with a knife and cut into a Boticelli. He removed the cut-away square of canvas, the head of Venus now disjoined from the luxuriant atmosphere of the larger painting where she’d lounged with Mars amid rampant cherubim. The camera then showed a printing press in action, the head of Venus copied again and again by machine. And now the viewer understood the room, the canvas, and the Venus as reproductions. This was the opening of the revolutionary Ways of Seeing series, much of which was filmed in the actual National Gallery.

n British television in 1972, standing in a room of the National Gallery, John reached up with a knife and cut into a Boticelli. He removed the cut-away square of canvas, the head of Venus now disjoined from the luxuriant atmosphere of the larger painting where she’d lounged with Mars amid rampant cherubim. The camera then showed a printing press in action, the head of Venus copied again and again by machine. And now the viewer understood the room, the canvas, and the Venus as reproductions. This was the opening of the revolutionary Ways of Seeing series, much of which was filmed in the actual National Gallery. “Reproduction,” John would write in the accompanying book, “isolates a detail of the painting from the whole. The detail is transformed. An allegorical figure becomes a portrait of a girl.”

“Reproduction,” John would write in the accompanying book, “isolates a detail of the painting from the whole. The detail is transformed. An allegorical figure becomes a portrait of a girl.”He was telling us what he would express elsewhere, some years later, in these ways:

With the loss of memory the continuities of meaning and judgment are also lost to us. The camera relieves us of the burden of memory. It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other god has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.” (“Uses of Photography,” 1978, in About Looking)

“The first step toward building an alternative world has to be a refusal of the world-picture implanted in our minds and all the false promises used everywhere to justify and idealize the delinquent and insatiable need to sell.” (“Against the Great Defeat of the World,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

emory implies a certain act of redemption,” John had written in 1978. “What is remembered has been saved from nothingness. What is forgotten has been abandoned. If all events are seen, instantaneously, outside time, by a supernatural eye, the distinction between remembering and forgetting is transformed into an act of judgment, into the rendering of justice, whereby recognition is close to being remembered, and condemnation is close to being forgotten.” (“Uses of Photography”)

emory implies a certain act of redemption,” John had written in 1978. “What is remembered has been saved from nothingness. What is forgotten has been abandoned. If all events are seen, instantaneously, outside time, by a supernatural eye, the distinction between remembering and forgetting is transformed into an act of judgment, into the rendering of justice, whereby recognition is close to being remembered, and condemnation is close to being forgotten.” (“Uses of Photography”)Memory, justice, silence, human compassion, the act of seeing, resistance, subversion, the restoration of the natural, communal, and sustainable — all were primary concerns in John’s essays and fiction.

In his 1995 novel To the Wedding, John invented his most gloriously imaginative and affecting narrator: a blind Greek peddler in Athens (Homeric echoes, yes) whose sensitivity to the passing voices of strangers enables him to see and listen into their personal histories and private moments, even to hear/see across the greater part of Europe to follow a few scattered members of a family as they journey to a wedding.

In his 1995 novel To the Wedding, John invented his most gloriously imaginative and affecting narrator: a blind Greek peddler in Athens (Homeric echoes, yes) whose sensitivity to the passing voices of strangers enables him to see and listen into their personal histories and private moments, even to hear/see across the greater part of Europe to follow a few scattered members of a family as they journey to a wedding.Early on the narrator explicitly informs us, “Blindness is like the cinema, because its eyes are not either side of a nose but wherever the story demands.” This touches on something far more subtle and suggestive than the tired ‘narration as camera’ analogy used with regard to fiction writing. Rather than the novelist pointing the ‘lens’ of his own narration here and there like an authorial movie camera, by giving us the intermediate consciousness of the blind Greek man he gives his story an expansiveness, a mysteriousness, a dimensionality of the kind that only fiction can give (and film and filmic conventions cannot).

Here’s a small passage:

The motorbike with its headlight zigzags up the mountain. From time to time it disappears behind escarpments and rocks and all the while it is climbing and becoming smaller. Now its light is flickering like the flame of a small votive candle against an immense face of stone.

For him it’s different. He is burrowing through the darkness like a mole through the earth, the beam of his light boring the tunnel and the tunnel twisting as the road turns to avoid boulders and to climb. When he turns his head to glance back — as he has just done — there is nothing except his taillight and an immense darkness.

We notice more keenly the blind man’s act of noticing and imagining than we would an author’s, because he seems to have no controlling interest. His stake in the story is pure. And we, in turn, want to listen and see and imagine as purely as he does. In other words, we want to care. And so we do: we enter the novel and we care. But somehow, too, when the story has ended, we bring that caring out of the book with us and apply it anew to the world.

The book itself embodies and teaches compassion.

n an essay on Géricualt’s portrait of a man with tousled hair (a painting from a series Géricualt made in a Parisian insane asylum), John marvels at the artist’s clarity, pity, and compassion:

n an essay on Géricualt’s portrait of a man with tousled hair (a painting from a series Géricualt made in a Parisian insane asylum), John marvels at the artist’s clarity, pity, and compassion:…A compassion which refutes indifference and is irreconcilable with any easy hope. … Compassion has no place in the natural order of the world, which operates on the basis of necessity. The laws of necessity are as unexceptional as the laws of gravitation. The human faculty of compassion opposes this order and is therefore best thought of as being in some way supernatural. To forget oneself, however briefly, to identify with a stranger to the point of fully recognizing her or him, is to defy necessity, and in this defiance, even if small and quiet and even if measuring only 60 cm. x 50 cm., there is a power which cannot be measured by the limits of the natural order. It is not a means and it has no end.” (“A Man with Tousled Hair,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

hank you,” I wrote to John in my letter, “for your novels, stories, poems, essays, and studies — and the clear sight and uncompromising spirit your work always exemplifies.”

hank you,” I wrote to John in my letter, “for your novels, stories, poems, essays, and studies — and the clear sight and uncompromising spirit your work always exemplifies.”In the parcel I’d also enclosed a copy of remarks I’d made a few days before, while introducing Partisans in a small public event at Powell’s Books. It’s fitting, I’d said to the ten or twelve people present that night, that we gather in this secret place, among real books, beyond the digital eye of the Network and the Market Optimization Bureau. Coming together here is a significant act of resistance. The future is upon us, and we need to stick together in these times — and in the times ahead. Tonight we remind ourselves of this because one of our own, one who went missing some time ago, has left us a manuscript.

I went on (to the mystification of some present) to speak of Geoffrey Peerson Leed, the disappeared author whose manuscript I had shaped into Partisans: One can learn a great deal about G.P. Leed — about his uncomfortable place in this future of ours — from reading his strange manuscript; I certainly have. But there is still a vast amount of things we cannot know, and nowhere in the rest of the archive are these questions answered. Who exactly was he? Where was he born? What was his childhood like? His homelife? What did he look like? How did he become the kind of writer he was? What were the exact circumstances of his disappearance? All questions without answers. But we have Partisans, and as we read it I think we come to feel that these specific things, these lacunae and redacted parts, are not so important. What matters and will continue to matter is the spirit of the man, the resolve he displayed in the face of all that opposed the work he was doing…

“There are two categories of storytelling,” John writes:

“There are two categories of storytelling,” John writes: Those that treat of the invisible and hidden, and those that expose and offer the revealed. What I call — in my own special and physical sense of the terms — the introverted category and the extroverted one. Which of the two is likely to be more adapted to, more trenchant about what is happening in the world today? I believe the first.

“Because its stories remain unfinished. Because they involve sharing. Because in their telling a body refers as much to a body of people as to an individual. Because for them mystery is not something to be solved but to be carried. Because, although they may deal with sudden violence or loss or anger, they are long-sighted. And, above all, because their protagonists are not performers but survivors.” (Bento’s Sketchbook)

am rereading his work this morning, as I’ve done so often before. The inflections are inevitably different, now that he’s gone — but the force of his inspiration only grows.

am rereading his work this morning, as I’ve done so often before. The inflections are inevitably different, now that he’s gone — but the force of his inspiration only grows.On the consolations of seeing:

In art museums we come upon the visible of other periods and it offers us company. We feel less alone in face of what we ourselves see each day appearing and disappearing. So much continues to look the same: teeth, hands, the sun, women’s legs, fish … in the realm of the visible all epochs coexist and are fraternal, whether separated by centuries or millennia.” (“Step Towards a Small Theory of the Visible,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

In art museums we come upon the visible of other periods and it offers us company. We feel less alone in face of what we ourselves see each day appearing and disappearing. So much continues to look the same: teeth, hands, the sun, women’s legs, fish … in the realm of the visible all epochs coexist and are fraternal, whether separated by centuries or millennia.” (“Step Towards a Small Theory of the Visible,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

I can think of no other European painter whose work expresses such a stripped respect for everyday things without elevating them, in some way, without referring to salvation by way of an ideal which the things embody or serve. Chardin, de la Tour, Courbet, Monet, de Staël, Miro, Jasper Johns — to name but a few — were magisterially sustained by pictorial ideologies, whereas he, as soon as he abandoned his first vocation as a preacher, abandoned all ideology. He became strictly existential, ideologically naked. The chair is a chair, not a throne. The boots have been worn by walking. The sunflowers are plants, not constellations. The postman delivers letters. The irises will die. And from this nakedness of his, which his contemporaries saw as naivety or madness, came his capacity to love, suddenly and at any moment, what he saw in front of him. …

As he sits with his back to the monastery looking at the trees, the olive grove seems to close the gap and to press itself against him. He recognizes the sensation — he has often experienced it, indoors, outdoors, in the Borinage, in Paris or here in Provence. To this pressing — which was perhaps the only sustained intimate love he knew in his lifetime — he responds with incredible speed and the utmost attention. Everything his eye sees, he fingers. And the light falls on the touches on the vellum paper just as it falls on the pebbles as his feet — on one of which (on the paper) he will write Vincent.” (“Vincent,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

That she became a world legend is in part due to the fact that in the dark age in which we are living under a new world order, the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refinding of dignity and hope. Much pain is unshareable. But the will to share pain is shareable. And from that inevitably inadequate sharing comes a resistance.” (“Frida Kahlo,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

Poems, even when narrative, do not resemble stories. All stories are about battles, of one kind or another, which end in victory and defeat. Everything moves towards the end, when the outcome will be known.

Poems, even when narrative, do not resemble stories. All stories are about battles, of one kind or another, which end in victory and defeat. Everything moves towards the end, when the outcome will be known.

Poems, regardless of any outcome, cross the battlefields, tending the wounded, listening to the wild monologues of the triumphant or the fearful. They bring a kind of peace. Not by anaesthesia or easy reassurance, but by recognition and the promise that what has been experienced cannot disappear as if it had never been. Yet the promise is not of a monument. (Who, still on a battlefield, wants monuments?) The promise is that language has acknowledged, has given shelter, to the experience which demanded, which cried out.

Poems are nearer to prayers than to stories, but in poetry there is no one behind the language being prayed to. It is the language itself which has to hear and acknowledge. For the religious poet the Word is the first attribute of God. In all poetry words are a presence before they are a means of communication.” (And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos)

You put something down and you don’t immediately know what it is. It has always been like that. … All you have to know is whether you’re lying or whether you’re telling the truth, you can’t afford to make a mistake about that distinction any longer.” (Here Is Where We Meet)

sometimes thought I’d write him a second letter — and maybe a third. My main impulse was to further express my thanks. I knew he was getting old, I’d heard something about his health concerns, but by all remote appearances he seemed as productive, alert, and articulate as ever. Surely there’d be plenty of time, and I felt certain he’d respond. Clearly he was generous that way. In just the few brief lines with which he replied to my parcel, John transmitted such humanity, such humility and understanding warmth, that I had no doubt he’d taken me in, that he would remember me now.

sometimes thought I’d write him a second letter — and maybe a third. My main impulse was to further express my thanks. I knew he was getting old, I’d heard something about his health concerns, but by all remote appearances he seemed as productive, alert, and articulate as ever. Surely there’d be plenty of time, and I felt certain he’d respond. Clearly he was generous that way. In just the few brief lines with which he replied to my parcel, John transmitted such humanity, such humility and understanding warmth, that I had no doubt he’d taken me in, that he would remember me now.Accept the unknown. There are no secondary characters. Each one is silhouetted against the sky. All have the same stature. Within a given story some simply occupy more space. (Bento’s Sketchbook)

ow many people did John touch directly, with that magnanimity, that same clarity of vision and heart that infuses his work?

ow many people did John touch directly, with that magnanimity, that same clarity of vision and heart that infuses his work?In reply to what I sent him John wrote, at 89 years old and in poor health, an expression of genuine gratitude:

Thank you so much for writing to me. Your letter was a great encouragement. It offered me energy.

Encouragement. Energy.

The stakes were high, the margin narrow. And in art these are the conditions which make for energy.” (“The Fayum Portraits,” in The Shape of a Pocket)

He said: And thank you for Partisans, where we’ll join forces.

And he wrote: We continue, yes? Yes.

presence, a visible presence, is sometimes most eloquently conveyed by a disappearance.

presence, a visible presence, is sometimes most eloquently conveyed by a disappearance.

Who does not know what it is like to go with a friend to a railway station and then to watch the train take them away? As you walk along the platform back into the city, the person who has just gone is often more there, more totally there, than when you embraced them before they climbed onto the train. When we embrace to say goodbye, maybe we do it for this reason — to take into our arms what we want to keep when they’ve gone. (“Will It Be a Likeness?” in The Shape of a Pocket)

M. Allen Cunningham is the author of six books, including the #1 Indie Next novel The Green Age of Asher Witherow (Unbridled Books, 2004); a biographical novel about Rainer Maria Rilke entitled Lost Son (Unbridled Books, 2007); and Partisans (Atelier26, 2015), a samizdat novel about unbridled surveillance, constant war, and maddening technological upheaval, which was a finalist for the Flann O'Brien Award for Innovative Fiction. He recently edited and wrote the introduction for a new collection of the humorous writings of Henry David Thoreau, the first volume of its kind (appearing November 2016). His work has appeared in many literary outlets including The Kenyon Review, Glimmer Train, Tin House, and Alaska Quarterly Review. The recipient of residencies at the Yaddo Colony and multiple fellowships and grants, Cunningham founded the independent literary press Atelier26 and is a contributing editor for Moss literary journal. He recently joined The Attic Institute as a Teaching Fellow, facilitates the Atelier26 Creative Writing Workshops, and teaches at Literary Arts.

M. Allen Cunningham is the author of six books, including the #1 Indie Next novel The Green Age of Asher Witherow (Unbridled Books, 2004); a biographical novel about Rainer Maria Rilke entitled Lost Son (Unbridled Books, 2007); and Partisans (Atelier26, 2015), a samizdat novel about unbridled surveillance, constant war, and maddening technological upheaval, which was a finalist for the Flann O'Brien Award for Innovative Fiction. He recently edited and wrote the introduction for a new collection of the humorous writings of Henry David Thoreau, the first volume of its kind (appearing November 2016). His work has appeared in many literary outlets including The Kenyon Review, Glimmer Train, Tin House, and Alaska Quarterly Review. The recipient of residencies at the Yaddo Colony and multiple fellowships and grants, Cunningham founded the independent literary press Atelier26 and is a contributing editor for Moss literary journal. He recently joined The Attic Institute as a Teaching Fellow, facilitates the Atelier26 Creative Writing Workshops, and teaches at Literary Arts.