Reading Lines

Reading Lines

Tidy Causal Packages

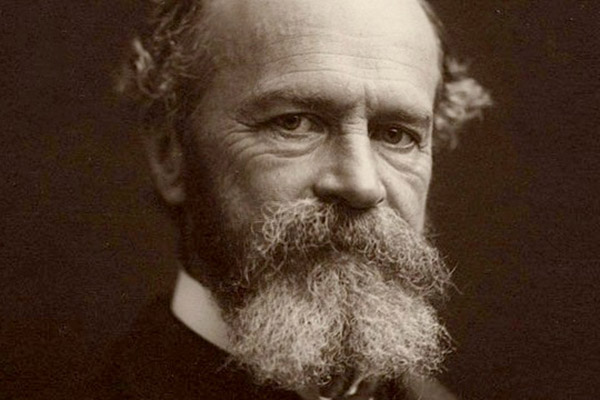

William James and the Perils of Theory

William James warned that pragmatism is a “turbid, muddled, Gothic sort of affair.”

William James warned that pragmatism is a “turbid, muddled, Gothic sort of affair.”By Wendy Bourgeois

s a kid I was a crier, a real Camille. I cried over baby animals. I cried when my parents fought. I cried if anyone was mean to me, or if I saw anybody be mean to anybody else. I could not watch M*A*S*H with the family because just the idea of war, even as a backdrop for punch lines, would have me in hysterics before the first commercial break. Nobody knew what to do with me. I wasn’t interested in riding a bicycle or doing anything with a ball. I had no siblings, and other kids in the neighborhood understandably found me offputting. I did like books, though, and living in the world of pretend, so I read and read and read, and in reading I found relief and, more importantly, control over the constant overwhelming intensity of my feelings. Are other kids like this? I’m not sure. I mean obviously they don’t all retreat from chaos into books (mine didn’t) but does everyone find learning to negotiate their feelings so impossible? I like to imagine kinesthetic types, dancers and basketball players and runners, have it easier because their whole bodies work to express the excesses inside of them. I mostly just have words pummeling me inside my brain.

s a kid I was a crier, a real Camille. I cried over baby animals. I cried when my parents fought. I cried if anyone was mean to me, or if I saw anybody be mean to anybody else. I could not watch M*A*S*H with the family because just the idea of war, even as a backdrop for punch lines, would have me in hysterics before the first commercial break. Nobody knew what to do with me. I wasn’t interested in riding a bicycle or doing anything with a ball. I had no siblings, and other kids in the neighborhood understandably found me offputting. I did like books, though, and living in the world of pretend, so I read and read and read, and in reading I found relief and, more importantly, control over the constant overwhelming intensity of my feelings. Are other kids like this? I’m not sure. I mean obviously they don’t all retreat from chaos into books (mine didn’t) but does everyone find learning to negotiate their feelings so impossible? I like to imagine kinesthetic types, dancers and basketball players and runners, have it easier because their whole bodies work to express the excesses inside of them. I mostly just have words pummeling me inside my brain.Turns out, reading was a pretty good strategy. I got the gold stars in school and eventually I even stopped crying. I think other kids still found me offputting, but I managed. Not until my thirties, when my therapist pointed out that I might “intellectualize my emotions” did I realize a potential downside to the chronic reading, which was that I habitually cushion myself from feeling with ideas, with argument. Theory as fear reducer and pain manager. In other words, I turned into a philosopher, and that’s not a good thing. According to William James, philosophers

have always aimed at clearing up the litter with which the world is apparently filled. They have substituted economical and orderly conceptions for the first sensible tangle; and whether these were morally elevated or merely intellectually neat, they were at any rate always aesthetically pure and definite, and aimed at ascribing to the world something clean and intellectual.

After our most recent quarterly mass shooting for example, when everyone else was weeping and calling loved ones and going to vigils, I stayed up late, unable to sleep while I developed a point-by-point refutation of the idea of subcultural co-option because I feared it would reduce the groundswell of empathy necessary to enact gun reform. And I didn’t do anything with it. I didn’t shed one tear; I didn’t write a congressman one check; I didn’t even write down the thoughts in a journal. I just thought them until I could sleep. That cannot be healthy.

f course any alcoholic can tell you that too much thinking is bad for you, but they don’t tell you what to do instead. James, bless him, offers an alternative, but it’s strong medicine. He says that compared with the pleasure of rationalizing, pragmatism, by which he means abandoning any hope that ideas can accurately correspond to a world “out there,” is

f course any alcoholic can tell you that too much thinking is bad for you, but they don’t tell you what to do instead. James, bless him, offers an alternative, but it’s strong medicine. He says that compared with the pleasure of rationalizing, pragmatism, by which he means abandoning any hope that ideas can accurately correspond to a world “out there,” isa turbid, muddled, gothic sort of affair without sweeping outline and little pictorial nobility, but one must live some time with a system to appreciate its merits.

James himself did not arrive at this conclusion without plenty of staying up nights theorizing, inexplicably and inescapably driven to spend his time thinking about how he might limit the prison of his thinking. Chronically depressed, he wrote volumes on the fuel of his restless misery. But notice those delicious adjectives, turbid, muddled, gothic. Those don’t come from analysis—they aren’t even rhetorically sensible. They are, as Richard Rorty says, “contingent” meaning balanced somehow between private nonsense and public communication, between meaning and not meaning, the language of artists, because artists recognize the inertia of perfected speech and closed systems. He says only poets can see the limits of the perfect and the closed, and the rest of us are “doomed to be philosophers.”

One minute, James lectures soberly; the next, he fills a page with lunacy.

One minute, James lectures soberly; the next, he fills a page with lunacy. ecently underemployed for some weeks, I found myself getting enough sleep and exercise, cooking every meal, having plenty of sex, not reading much of anything, and generally just catering to the wants of my animal body. I had such plans for that time. I was going to submit my manuscript and write a new one and update my resume and attend every meeting instead of dodging them like usual and possibly find a new career in marketing that would pay off my student debt and allow me to—what, exactly? Retire? Live on a houseboat and whittle? Devote myself entirely to internet shoe shopping? Die? I occasionally cast about in my notebooks for something of interest to say, and wow did I have fuck all. All my reason and reasons looked trivial. I re-read my poems and saw with some distress that every single one of them was an argument designed to explain away a wound or mystery. There’s me, The Little Engine That Could, chuffing away in search of praise and answers and perfect understanding, even when I’m trying to make art.

ecently underemployed for some weeks, I found myself getting enough sleep and exercise, cooking every meal, having plenty of sex, not reading much of anything, and generally just catering to the wants of my animal body. I had such plans for that time. I was going to submit my manuscript and write a new one and update my resume and attend every meeting instead of dodging them like usual and possibly find a new career in marketing that would pay off my student debt and allow me to—what, exactly? Retire? Live on a houseboat and whittle? Devote myself entirely to internet shoe shopping? Die? I occasionally cast about in my notebooks for something of interest to say, and wow did I have fuck all. All my reason and reasons looked trivial. I re-read my poems and saw with some distress that every single one of them was an argument designed to explain away a wound or mystery. There’s me, The Little Engine That Could, chuffing away in search of praise and answers and perfect understanding, even when I’m trying to make art. Maybe I am doomed to be a philosopher. “The radical pragmatist” (or she who has successfully cut ties with theory), James says, “is a happy go lucky, anarchistic sort of creature, adrift in a tramp and vagrant world.” Sounds like a Springer spaniel, but I can practically taste the longing in his voice. James was not that kind of pragmatist. He got shit done. Even though somehow, inadvertently, right there in the middle of his earnest striving, his language always runs away with him. One minute he lectures soberly on the nuances of Hegel and Humanism, and the next, he fills a page with lunacy, mocking what he calls “abstraction worship” with wild metaphors like “the bellyband of the universe must be tight” and “every drop of blood stamped and branded.”

This doesn’t sound to me like someone getting away from the intensity of feelings by theorizing. It sounds like someone falling face first into them while looking for something else. All that strange, iconoclastic whimsy—poetry disguised as philosophy, maybe. I guess what I am trying to say (besides William James is awesome, seriously, go read some William James) is that I may have just realized that I can meditate and eat gummy worms and roll around in the grass all I want but I still won’t be that blissful pragmatist, not even a little bit zen. I still can’t watch more than one episode of Game of Thrones at a time without being paralyzed by sorrow at the human condition. I’m just not a happy go lucky, anarchistic girl. I need those theory engines firing if I ever want to get to the art or find the feelings. And it’s embarrassing and weird just like it was when I was ten, but there’s no escaping it.

Wendy Bourgeois is a poet and writer. In the winter issue she wrote about a line from Brenda Shaughnessy.

Wendy Bourgeois is a poet and writer. In the winter issue she wrote about a line from Brenda Shaughnessy.