Late Night Library

Unions and Allies

Late Night Library Calls It a Day

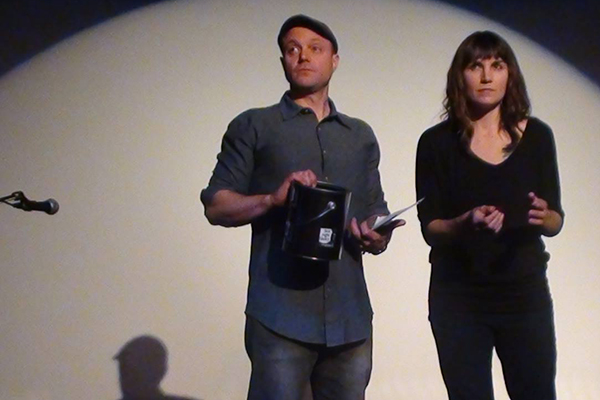

Paul Martone (left) and Margaret Malone (right) at the book-themed variety show “All Fines Forgiven.”

Paul Martone (left) and Margaret Malone (right) at the book-themed variety show “All Fines Forgiven.”By Patrick McGinty

s of 9:00 p.m. on Tuesday, October 18th, faculty at the fourteen state-owned universities in Pennsylvania were still without a new contract. The sticking points in the union’s negotiations with the state education system were not surprising to anyone familiar with higher education—adjunct workload, retrenchment, healthcare, so forth. What was more surprising was the length of the negotiation process. Negotiations had failed with such regularity that the 5,000 member faculty union known as APSCUF had wound up working for 476 days without a contract. A strike was scheduled for the 477th day at 5:00 a.m.

s of 9:00 p.m. on Tuesday, October 18th, faculty at the fourteen state-owned universities in Pennsylvania were still without a new contract. The sticking points in the union’s negotiations with the state education system were not surprising to anyone familiar with higher education—adjunct workload, retrenchment, healthcare, so forth. What was more surprising was the length of the negotiation process. Negotiations had failed with such regularity that the 5,000 member faculty union known as APSCUF had wound up working for 476 days without a contract. A strike was scheduled for the 477th day at 5:00 a.m.I was at home on Tuesday night, double-checking my strike shifts inside a complex, immaculately arranged Google Doc. The weather app I thumbed was inconclusive.

As someone new to the union, I had been fielding questions from friends and neighbors as to whether I, as a full-time but temporary faculty member, would cross the line. What if the strike was held against me during review? How could I possibly afford to give up our healthcare with a wife who was eight-and-a-half months pregnant? My answer usually involved heritage. My grandfather, I’d say, went on multiple strikes at a mill ten minutes from the university. I figured the noble, Rust-Belt dots could be connected from there, though this reasoning never rang right with me. One of the truer likelihoods for my eagerness to strike is that I am an exaggerator of the highest order, a truly obscene manipulator of details, and as such, I’m adept at spotting ‘story kernels’ that I can then grow into a whopper—Well, son, you were pushing your way on out into the world, but I owed it to the union to march. You think I’m kidding.

My wife handed me her laptop. “Read this,” she said.

The news was not strike-related. The news concerned the dissolution of Late Night Library, an organization which our household has a rather significant stake in. The most basic, stripped-down rendering is to say that I once hosted a few LNL podcasts and served as a reader for the “Debut-litzer” prize; my wife began as a managing editor, then co-hosted and produced the Late Night Love Affair podcast until we left Portland. In the early days, the organization got its name by releasing podcasts at midnight once a month. They focused on debut writers, whose books, the originators felt, needed all the attention they could get. The organization achieved 501(c)(3) nonprofit status. Then they began a visiting writers series. Then they started a book club. And off-shoot podcasts. There were blogs. And vlogs. And really fun nights dubbed “book-themed variety shows.” Late Night Library became the first organization in Western Civilization to host consistently fun, meaningful, unpretentious literary events.

I made a strange, sad groan while slowly reading the farewell post. My wife told me to stop, that it was creepy. I tried a different weather app and went to bed. When I woke, I read the APSCUF tweet from 4:59am, which announced that APSCUF was on strike. I checked the weather on my phone, then on our porch, and drove to the line.

Candace Opper in an advertisement for Late Night Library.

Candace Opper in an advertisement for Late Night Library. t’s worth noting that, forthcoming idealism not-withstanding, a good portion of the time spent on a picket line is rather boring, particularly when it rains. You pace. You change direction, then pace some more. You adjust your hood and, yup, it’s still raining. Down time is the norm.

t’s worth noting that, forthcoming idealism not-withstanding, a good portion of the time spent on a picket line is rather boring, particularly when it rains. You pace. You change direction, then pace some more. You adjust your hood and, yup, it’s still raining. Down time is the norm. To avoid thinking about the potential of my wife going into labor as well as the COBRA notice en route to our mailbox, I allowed my mind to drift. I made small talk. I whistled. In need of distraction, I observed the small college town as intensely as possible. Ninety-five percent of students had a phone in their hand as they drove, which seemed both obvious and insane. Ninety percent of our picket signs had duct tape lassoed around the splintery handles, which seemed both obvious and brilliant. People shouted things from cars. Most drive-by commentary was supportive, some was quite the opposite, and I was again reminded that people feel more rhetorically confident inside a moving vehicle than perhaps anywhere else. Are cars, I hypothesized, the original Facebook post?

These bored moments of non-sensical analogies were rare. Or they were for me, at any rate. The truth is: the strike was magical. I think I am now of the sincere opinion that every American should go on strike at some point in their lives. Strikes are a focused work retreat with none of the ropes courses or whiteboards. It is exercise, for God’s sake. It’s enlivening. If nothing else, a strike clarifies the math when it comes to one’s allies. Much mention is made in strike workshops and strike documents about the importance of assembling “allies,” so much so that at a certain page these admonitions risk falling into that dusty mental bin of oft-repeated, scantly-abided advice—your oil changes, your dentist’s appointments. Burdensome stuff.

But allies are not burdensome. Third-party allies are the grease required to move the stubborn gears of any immobilized relationship. With management and labor unwilling to budge, students from the Pennsylvania state system applied their leverage. Large numbers of students marched with the union. Impromptu bands appeared, played, then left as quick as bandits. Others lingered. A girl on crutches brought me hand warmers. Students I knew brought me pizza. Students I didn’t know brought me pizza. So many students baked or bought food as a show of support that I felt obligated to eat everything I was offered. The full tally from my twelve total hours on the picket line looks like: one hot dog, one piece of Domino’s pizza, one red velvet cupcake, one Oreo cupcake, two macadamia nut cookies, two Dunkin’ doughnuts, three cups of coffee, two waters, a single Twizzler, a piece of Coffaro’s pizza, and more chocolate chip cookies than I can remember. In my defense, I was on my feet for two six-hour shifts, arms astretch.

Whenever I lowered my arms to eat, a student or colleague would usually sidle up with a phone. They’d show me a clip of a massive student march being held on a different state campus. Students with hilarious if inappropriate signs pasted their supportive images on social media with the intention (as opposed to fear) of their likeness spreading widely and rapidly. By all metrics, the willingness of students to sacrifice their spare change in the name of Sheetz apple fritters and their likenesses to the internet should not carry equal weight to faculty jeopardizing their pay and healthcare. By all metrics, the contributions of students should have simply lifted the spirits of the union so as to spur more spirited marching.

Yet given the level of student support witnessed across the state, and given that the constant student visits to the capitol building and to the faculty picket lines helped end the strike in three tidy days, my metrics constituting “meaningful” and “effective” action have been thoroughly debunked. Third-party food, tweets, warmth, emails, and honks aggregated into a formidable presence in the negotiations. What’s more, the students were unpaid. They paid for things, unprompted. I had driven to the line impressed by the union’s commitment to quality education. I marched in awe of the allies.

thought often of Late Night Library while on the line. Was Late Night Library an unofficial kind of union? Was it a heroic third-party ally? And an ally to what, exactly? Were debut writers the union? What role did the publishers play?

thought often of Late Night Library while on the line. Was Late Night Library an unofficial kind of union? Was it a heroic third-party ally? And an ally to what, exactly? Were debut writers the union? What role did the publishers play? For much of Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, this thought exercise wasn’t particularly enlightening. Part of the difficulty in analogizing an entity to Late Night Library stems from the difficulty in precisely stating what exactly Late Night Library “was.” From my station on the periphery, the central premise germinated from changes that took place in the publishing industry post-2008, when an unprecedented number of debut writers, presses, and technological avenues coincided with an unprecedented dearth of industry funds. Faced with new technological options, the debut writer could adopt one of two general attitudes, each of which came with problems:

1) I have an online “presence,” but how do I stand out when there are so many of us?

2) “Online presence” is the most repugnant phrase in our society, and I will die my noble unread death on this shadeless hill.

This, to me, was the fundamental riddle that Late Night Library helped solve for many writers. By embracing podcasts so early and enlisting a large-hearted cast of writers, readers, and teachers, Late Night Library could function as the most well-intentioned and technologically savvy PR operation a debut writer could hope for. Late Night Library made a writer feel as though their work was being critically and commercially championed by a really smart, dedicated colleague.

Paul Martone, creator and executive director of Late Night Library.

Paul Martone, creator and executive director of Late Night Library. t is impossible to talk about the organization’s specific brand of dedication to literature without also saluting Paul Martone, the original Literary Citizen, that indefatigable enemy to stillness, a McG-Opper paisan for life, a man whose accomplishments and convictions I am limiting to a small closing section so as to not tiptoe into hagiography. Yes, he was a pioneer of the literary podcast, but he brought so much other tangible good into the literary world. Paul found roles for so many individuals within Late Night Library. He found paying work for his people outside of Late Night Library. Multiple volunteers for Late Night Library wound up with paid careers in the arts. These are not small accomplishments. These are Herculean efforts that have paid specific dividends to literature and to the people who endeavor on its behalf.

t is impossible to talk about the organization’s specific brand of dedication to literature without also saluting Paul Martone, the original Literary Citizen, that indefatigable enemy to stillness, a McG-Opper paisan for life, a man whose accomplishments and convictions I am limiting to a small closing section so as to not tiptoe into hagiography. Yes, he was a pioneer of the literary podcast, but he brought so much other tangible good into the literary world. Paul found roles for so many individuals within Late Night Library. He found paying work for his people outside of Late Night Library. Multiple volunteers for Late Night Library wound up with paid careers in the arts. These are not small accomplishments. These are Herculean efforts that have paid specific dividends to literature and to the people who endeavor on its behalf. Driving home in the rain on Friday, the strike over, the union victorious, I decided that Paul was Late Night Library management, and he was also labor, and he was also the ally, for both his organization and for its staff and for the writers Late Night Library championed. He greased the gears for all parties. Things will feel more rigid without he and Late Night Library rushing to the literary line.

Patrick McGinty’s fiction has appeared, most recently, in ZYZZYVA and The Portland Review. He recently pointed out that even though we are all exhausted by the election, political pundits actually wanted it to be longer.

Patrick McGinty’s fiction has appeared, most recently, in ZYZZYVA and The Portland Review. He recently pointed out that even though we are all exhausted by the election, political pundits actually wanted it to be longer.