Film

IN THE MIDDLE of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, a photographer parked on a London street sees a woman he’s been looking for. As the woman looks in a shop window, passing pedestrians obscure her from our view for a moment—and when the pedestrians clear, the woman is gone. The photographer crosses the street to the spot where she stood, but finds no sign of her. It’s the last we see of her in the film.

It’s also the most conspicuous instance of what have been, throughout the film, a series of erasures. An early one occurs during the film’s opening sequence, when the photographer, played by David Hemmings, is confronted by a group of students celebrating Rag Week. Dressed as mimes, the students demand money (ostensibly for charity), and the photographer hands them some bills. But how many students are there? One particular student seems oddly blocked from our view. Later in the film, the photographer watches trees rustle in the breeze in an empty park where earlier he had watched (and photographed) a woman walking with her lover. His perception of the event has been altered, though, because he now knows there were more than two people present. And maybe the man and woman weren’t lovers. Oh, and also, he discovered a dead body—but then the body disappeared. Each time the photographer confirms an item of fact, the fact wobbles, or its marks are erased. The photographer’s investigations result in knowledge, but no evidence. He cannot prove anything.

The history of narrative film, and perhaps of narrative in general, is dominated by creators who claim or imply that their stories impart useful life lessons. Antonioni doesn’t seem interested in film as a delivery device for truisms, though. His films operate more in accord with Dziga Vertov’s famous manifesto-documentary Man with a Movie Camera, a disquisition on the experiential possibilities of cinema and the ways in which the form offers an aesthetic experience wholly different from that of literature or theater. Angles of approach, editing techniques, choices in exposure and shot duration: cinema offers audiences the power to be anywhere, see anything, Vertov suggested. Moving pictures were an entirely new, unprecedentedly penetrating level of experience.

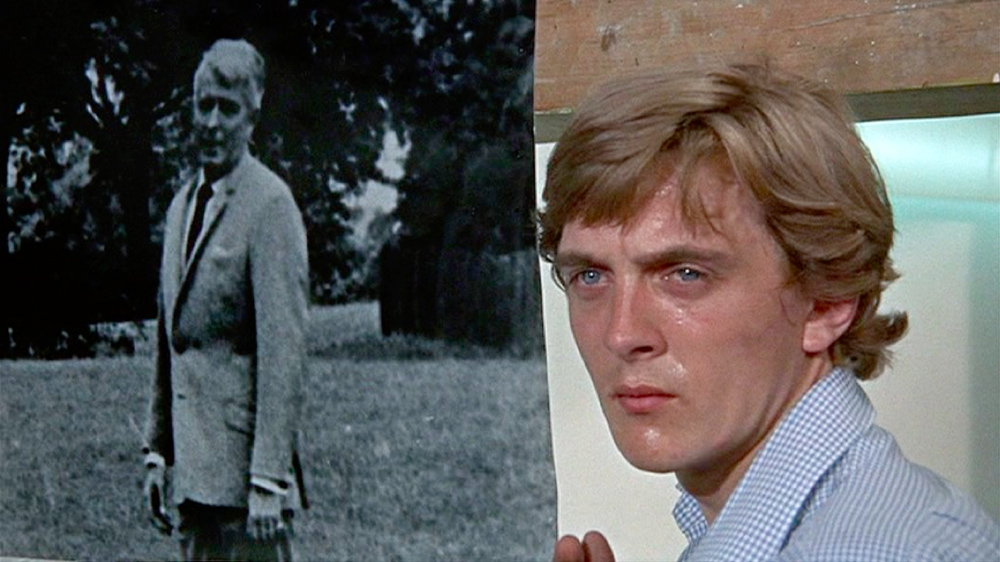

Blow-Up proceeds according to the content of Vertov’s lesson, but the result is the opposite: the man with the camera doesn’t necessarily see anything. Thomas, the photographer, takes photos of people—significantly, of women and the poor—but he doesn’t really see or care about them. Most Antonioni films trouble our desire to identify with the protagonist, and that is certainly the case here: David Hemmings, in a role he would be identified with for the rest of his career, enacts Thomas as a barking, impatient, condescending young man entirely in thrall to the power of his own aesthetic abilities. (The character is supposedly patterned after David Bailey, an actual photographer of the London fashion scene.) He doesn’t interact with anyone as if they are equals, but instead as if their existence is limited to one of two categories: potential photographic assistants, or potential photographic subjects.

In a mesmerizing extended sequence, we watch Thomas at work in his darkroom, utilizing all of the chemical powers of photography: developing negatives, dodging and burning prints, and, of course, creating blow-ups. The sequence reveals that the creation of an image is actually the result of a process that first involves investigation: searching a negative for what might be found within. Craft and artifice create a presentation—a new image—of what was discovered in the investigation. By presenting images as representations and interpretations rather than facts, Blow-Up anticipates much of the trouble of our contemporary moment, in which we live besieged by images and their supposed gift to take us anywhere, show us anything. The gift has not given us superior insight or truth. Instead, we increasingly live with a suspicion that none of the images we are shown capture the truth of an event. What really happens, it seems, is something we can’t see.

THE FIRST TIME I saw Blow-Up was actually the second time. A particular scene tipped me off: Thomas hears a knock on the door of his studio and answers it to find two young women. Within a couple minutes, all three of them are wrestling on the studio floor, a rack of stylish dresses toppled as they pull each other’s clothes off. I recalled seeing the scene on television when I was a kid—it’s not the kind of thing a boy forgets discovering while flipping through channels. I’d been old enough to understand the movie suggested the three of them had sex, and to suspect some nudity had been cut so the film could be broadcast on over-the-air television in the 1980s. (My family lived beyond the reach of early cable television.) I had no memory of anything else from the film, though. When ensuing scenes lacked similar material I probably changed the channel, and in those years, if your family didn’t get TV Guide and the newspaper television grid listed the program only as “Saturday Afternoon Movie,” there was no easy way to find out what you were watching. So I didn’t.

When I prepared to watch Blow-Up years later, however, I approached it from a different angle. Because Antonioni’s L’Avventura often appears on lists of best films, I’d rented it from the video store and discovered a movie with material I found recognizable—characters who felt frustrated and lost—but that also included other, more troubling energies. Alienation, modernity, and ennui are the terms that almost always appear in discussions of Antonioni, but they strike me as equivalent to what the term twee has become to the films of Wes Anderson: words movie reviewers repeat as stand-ins for what they can’t explain or decline to discuss. Antonioni himself, after the audience at Cannes booed the first screening of L’Avventura, suggested that part of the difficulty may have had to do with narrative expectations—he described the film as a “noir in reverse.” I’d dutifully rented La Notte, L’eclisse, and Red Desert, and saw in them further variations on the theme. When the protagonists in these films investigate something—the truth behind a woman’s disappearance, the state of a marriage, the source of loneliness—rather than moving toward a cause or answer, the investigators instead become further mystified or, in contemporary psychological parlance, more deeply enmeshed.

“The film is suspicious of popular versions of the 60s that present liberation as looking something like perusing Playboy magazine before dropping a tab of acid in search of higher consciousness.”

Cueing up Blow-Up, I expected a departure. Antonioni’s first English language film, and only his second in color, Blow-Up, too, appears on many lists of best films. The graphically bold simplicity of its best-known poster, in which Hemmings straddles the model Veruschka as he trains his camera on her, and the film’s association with the mod London of the 1960s suggested something different from the coiled anxiety of Antonioni’s previous films. Since Antonioni wasn’t an authority on contemporary British slang or diction, the actors would have had room to shape their lines and interpretations. Likewise, the film’s cinematographer, Nicolas Roeg (who would later direct his own remarkable films), was certainly as knowledgeable as Antonioni about the film stock they were using, which would have allowed Antonioni to concentrate on the problems of attention and perception that so interested him. And finally, Blow-Up does not feature Monica Vitti, Antonioni’s cinematic muse and romantic partner, who warmed the centers of his previous four films. Blow-Up doesn’t feature a strong feminine presence at all, in fact—a departure from all previous Antonioni films. (Vanessa Redgrave, who plays the woman the photographer captures in the park, but who later eludes him on the street, is in the movie for just a few scenes.) By removing himself from his comfortable context—the Italian film industry, the crews he’d worked with, the actors he was familiar with—Antonioni provided himself with a clean slate.

He then poured the colors and fashions of mid-60’s London across that slate. Mod, swinging London has been lampooned into cliché now—the Beatles did it in Help! long before Mike Myers circled back to pick up more laughs in the Austin Powers movies—but there’s a more troubled energy in the non-comedy films from the period. San Francisco’s summer of ’67 and the muddy 1969 Woodstock festival had yet to occur when Blow-Up was being made, so the 1960’s hadn’t yet acquired the tie-dyed-pastoral brand marketed to the world ever since. Blow-Up is marked by a sweaty tension that remains unfocused and directionless. The American version of the 1960s is famous for a slogan that is really just a list: sex, drugs, rock ’n roll. In Blow-Up, all three of those items are presented as distractions: Vanessa Redgrave takes her shirt off only because she’s trying to get the photographer’s film from him, partygoers are too stoned to care about what’s going on, and Antonioni presents a rock concert as a “rock concert,” with an audience entirely stupefied by the spectacle until the moment a holy relic (a piece of Geoff Beck’s smashed guitar) is cast at them. Devoid of joy or sentimentality, the film is suspicious of popular versions of the 60’s that present liberation as looking something like perusing Playboy magazine before dropping a tab of acid in search of higher consciousness. The concertgoers in Blow-Up are not enlightened, and the drugs lead nowhere.

This may be why there’s such a chasm between the popular and critical reception of the film. General audiences—especially first-time viewers—follow what appears to be a very slow thriller, and therefore expect to find out what was going on between the people in the park. If a crime was committed, who committed it, and why? This version of the film is just a story that doesn’t resolve, bookended by odd bits with mimes. Visual pleasures can’t fill the gap, because through this lens the movie appears hopelessly dated, the clothes, cars, and lingo reduced to historical affectations presented via characters that are arrogant, odd, stoned, or disappear. Once viewed (or abandoned), the movie can be safely filed away with other cinematic Anglophilia, perhaps on a shelf with the early Bond films, Modesty Blaise, and Quadrophenia.

Critics, on the other hand, read the film as a critique of the possibilities and limits of photography. By extension, then, it’s a movie about movies, and in this mode Blow-Up can seem like Antonioni finally synthesizing the subject matter of his previous films. By folding rock music and swinging London into the ennui, he successfully foregrounds the noir-in-reverse as a social condition rather than a personal problem. The British 1960’s get to be just as coolly disaffected as the Italian 1950’s, and the movie-about-photography gives the whole thing an academic (rather than an existential) sheen: the more we look into things, the less we’re going to find, and that’s cameras! One can then close Playboy long enough to intone that in Antonioni’s films, the ultimate discovery is that there is no meaning, after which one resumes the liberated evening ritual of preparing the favored drug and settling onto the couch in order to become stoned, immaculate.

This knowing, critical version of Blow-Up is not beloved by general audiences. It’s built on a critique of the power dynamics bound up in what cinema academics call “the look,” as well as what has passed into general use now as the concept of “the male gaze.” (The latter is of course a term that started in film criticism, though when Laura Mulvey coined it in 1972, she was referring to the way in which the camera, in Hollywood narrative films, presumes a male audience. The increasing contemporary use of the term as synonymous with “how straight men look at women” elides Mulvey’s central point about how it’s the technologies of filmmaking, and the industry that has sprung up around it, that are bound up in the ongoing objectification of women.) Audiences will allow a movie that critiques the act of looking only as long as that critique is at some point neutered by a story in which actually, looking at women saved the day. Hitchcock’s Rear Window is probably the most famous of the films that drop the critique in favor of the looking, though plenty of others follow the same pattern. Ultimately, these films have their cake and eat it, too—they offer just enough wryly intellectual content to give them the right amount of gravitas, but jettison that approach at some point in order to give the audience what it wants: the narrative thrills that come from placing a woman in peril and then heroically solving the mystery and winning the day—in other words, the exact fantasy that was supposedly being critiqued. The audience gets the happy ending it wanted, and laughs at the idea of serious reading:

If Blow-Up were nothing more than a movie that suggests artistically-inclined young men who behave badly will someday get their comeuppance, though, that would of course be fine, but probably not necessary for contemporary audiences to watch—there are plenty of films in which men behave badly and get their comeuppance. Likewise, if Blow-Up was just a critique of the power dynamics bound up in looking, that might be salutary, but also probably didactic and condescending. Critical essays on art can be handled quite well in the form of critical essays on art, and probably don’t need to be disguised as narrative films. What keeps me watching Blow-Up more than fifty years after it came out is how the film takes on an issue particularly acute in our contemporary moment: the problem that comes with realizing power is structural rather than personal.

The erasures, disappearances, and abstractions that occur in the film point more and more insistently to not just the existence, but also the controlling influence in our lives of forces that are unrepresentable. This is tricky territory for a filmmaker. What is a director to do when he wants to incorporate into his images the presence of forces that cannot be captured in images? When the photographer goes in search of a body later in the film, one of Antonioni’s strategies floats past: the sign that does not symbolize.

“I didn’t want people to be able to read that sign. Whether it advertised one product or another was of no importance. I placed it there because I needed a source of light in the night scenes,” Antonioni said in a 1969 interview. I’m going to claim that the second sentence is a lie. (Antonioni often refused to interpret his films, or acted casual about aspects of them that people on his sets revealed he was in fact very exacting about.) For this sign that looms over the park where the photographer took the photos that have now become the center of his investigation, Antonioni requested the creation of a sign with abstract letterforms that do not conform to any actual language. Other strategic employments of abstraction are also woven through the film—the photographer’s neighbor, for instance, is an abstract painter who says of his pieces, “They don’t mean anything when I do them. Just a mess. Afterwards, I find something to hang on to. [...] Then it sorts itself out and adds up. It’s like finding a clue in a detective story.” Antonioni’s attraction to abstraction isn’t specific to Blow-Up, of course—most of his films are marked by moments in which the frame is filled by what the eye first reads as an abstract image: the surfaces of walls, empty landscapes, or the back of a person’s head. In Blow-Up, however, the scale of abstraction—of the unreadable, or at least of that which requires careful, considered reading—is raised from objects or individuals to the level of crowds.

As the Yardbirds play in a club, Antonioni creates an artificial tableau in which the audience appears frozen, hypnotized (or lobotomized) by the spectacle before them. And though spectacle can momentarily invest something concrete (that piece of Beck’s guitar, for instance) with significance, outside the context of the spectacle, the significance evaporates. All that sweaty desire, it turns out, was temporary and disposable.

After the photographer realizes that not only has he not solved any mysteries, but that no one is going to listen to him and he is not going to be any kind of hero, he returns to the park. It is morning, and as he stands beneath the sign, it turns off for the day, actually becoming more visible, in the daylight, when unilluminated.

By this point in the film, the photographer has no further clues to what he captured in his lens, and no way forward. There is no stirring final sequence in which the killer is pursued and caught, and no denouement in which we see a man and woman united. Instead, the accumulation of absences and erasures leads to a final sequence in which the photographer is invited to decide whether he is going to play ball—not with some known nefarious entity, but instead while aware that he will never know, and will never see, what the game revolves around. In Blow-Up, not only does the individual have no effect on changing the system, but the individual’s very belief in his active and heroic individuality is revealed to be just one more part of the game. That the film ends with an evocation of a 1966 version of virtual reality is not an accident. What’s clear in Blow-Up is that the decision to behave as if elements that are clearly absent—whether justice, intelligence, earned authority, or moral guidance—are in fact present and operational is hardly a recent phenomenon.

It would probably be more elegant to end this article there, with that vague gesture in the direction of an aestheticized futility. But why be vague? Who, for instance, are the private equity firms or “angel investors” that provide the millions—or in many cases, the hundreds of millions—of dollars necessary for tech startups to spend years operating at huge losses while pursuing unethical and predatory business practices designed to slowly bankrupt small business owners? Who are the entities funding the lobbyists who continue to convince cynically craven or shockingly uneducated politicians to undo the laws and regulations designed to protect the country’s citizens? Who are the people negotiating the weapons and construction contracts to entities whose entire business models are built on profiting from war? Not only do we not see the people pulling the levers, but in many cases it seems that the original “disruptors” of democracy have moved on, and it is no longer mere individuals who need to be stopped, but instead entire corrupt supply chains and venal systems of influence. To continue on this track would be to move beyond the confines of film criticism. What I know is that I, as an individual, cannot heroically solve any of these problems on my own. And to document the problems solely for the purpose of hanging exquisitely composed, perfectly exposed takes on studio walls is hardly going to help. This essay, for example, will change nothing.

So if Blow-Up is about self-deception and futility, then why do I keep watching it? For all of the reasons above, I suppose, but also because rather than the neatly tied ending favored by so many other filmmakers, Antonioni allows the narrative energy to play all the way out. In a society that seems to suggest the best way to live involves watching YouTube life hacks, reading books on how to be happy, and preparing to give a charismatic TED talk, what about those of us who identify not with proficiency, efficiency, and mastery, but with doubt, uncertainty, and difficulty? What is absent from the faces in the Yardbirds audience is, by the end of the film, present in David Hemmings’ gaze. The photographer appears to have earned as his prize something that looks like what people used to call melancholy, a state I don’t hear much about these days, but which in former times was quite common among adults. It may be that I keep watching Blow-Up not just for its smart investigation of image, power, and erasure, but because there is a satisfaction—maybe even a comfort—in watching a film that lives with the repercussions of its approach. If you can’t beat the game of virtual reality, maybe there’s something to be said for becoming one of the many who don’t play. The reward is that you disappear.

Dan DeWeese’s new novel, Gielgud, will be in wide release in May. (Stores in Portland, Oregon, have it now.) He is also the author of the novel You Don’t Love This Man and the story collection Disorder.